Offbeat Paris News...

Read the script of Hugh Oram's recent lecture on Patrick Kavanagh given to the Irish Byron Society.

The first and only

time that I met Patrick Kavanagh was totally unforgettable, for all the

wrong reasons. The great poet certainly lived up, or perhaps down, to his

reputation!

It was at Queens

University in Belfast, where I was attending a seminar in the company of a

great friend and mentor, a professor of English called Alan Warner, who knew

Kavanagh well and who went on to write several books about him. He’d got off to

a rocky start with the Monaghan poet, because when Alan had decided he was

going to do a biography of Kavanagh, he started writing to all the relatives

and friends of the poet, something that immediately raised his hackles. It was

only too easy to provoke Patrick Kavanagh and the slightest perceived insult to

him, whether imagined or not, was enough to set off one of his tirades.

That’s all digressing

a little. By the time of that seminar in Queens, Alan Warner and Patrick

Kavanagh were on good enough terms with each other, as things had calmed down

quite a bit. Alan went on to write rather copiously about the poet, a few more

titles to add to the great corpus of works about the man from Monaghan.

Alan Warner had said

to me that day in Belfast: “I see Patrick Kavanagh in the distance, would you

like to meet him?” Always game for a challenge, I agreed and Alan Warner

negotiated himself to be near Kavanagh. He said to the poet “I’d like you to

meet one of my students, who has a great interest in literature, especially

Irish”. All very polite, except that Kavanagh’s response was anything but

cordial or polite. He simply turned his back on Alan Warner and myself and

stalked off in high dudgeon towards the far distance, muttering imprecations, probably

most foul.

That, I’m afraid, was

my one and only meeting with Patrick Kavanagh, but needless to remark, in the

intervening years, I’ve heard numerous stories, mostly scurrilous, about him.

Once, a noted

designer in the book trade who was a great friend of mine, told me, hand on

heart, of the time that Patrick Kavanagh was in McDaid’s pub just off Grafton

Street. A group of fellow poets there decided that it would be an excellent

time to take the piss out of Patrick Kavanagh. They bet him a shilling that he

wouldn’t shit on the floor. Always happy to earn money however and whenever he

could, he did the unmentionable and the unthinkable and put the shilling in his

back pocket.

Another anecdote I

heard about him concerns the time that he was in the old Country Shop on St

Stephen’s Green. He was working in journalism at the time and was getting a

reasonable amount of money so it was time for him to act reasonably posh. However,

that didn’t stop him propositioning a young actress - I knew her well in her

later years - and the mere fact that she had just had her first child was no

impediment. In his uncouth voice, he asked her straight out if she would have

sex with him in exchange for a fiver. In those days, a fiver was a lot of

money, a week’s wages, but the offer was declined.

Funnily enough, at

that time, in the early 1950s,Kavanagh was a frequent and willing participant

in the activities of the Catacombs in Fitzwilliam Place. This was a

marvellously uncouth basement place where the literati of the day descended

every night for drinking sessions and frequent couplings between men and women

and between people of the same sex. Kavanagh obviously had fun there, as did

everyone else, but this episode in Kavanagh’s life, indeed the Catacombs

themselves, have been largely airbrushed out of literary history.

At this stage in his

life, Kavanagh had a very hostile and truculent attitude of mind towards fellow

writers, the establishment, anyone you care to name, an attitude that had

started to surface in the mid-1940s. Kavanagh indeed became so critical of

everyone that he quite happily snapped at the hands that fed him. The financial

disaster that was the 13 issues of Kavanagh’s Weekly in 1953 was merely a

symptom of this truculence and at the bottom of it all, Kavanagh always played

the part of the ignorant and uneducated country person to perfection.

To the end of his

life, Patrick Kavanagh remained the uncouth countryman and I can’t help but

make the contrast with Seamus Heaney, who was born a mere 30 years later than

Kavanagh. Both had very similar rural upbringings, but the contrast in how they

turned out couldn’t have been more pronounced. Kavanagh was brought up in a

poor rural household in County Monaghan, where he proved immensely clumsy on

the farm and at helping his father mend shoes. Heaney was brought up in a rural

household in County Derry. Kavanagh never had the chance to progress much

beyond first level education. But ironically, Heaney, who always wrapped the

green flag around him, benefitted hugely from the university system in the

North, as symbolised by Queens. That university system, and the grants provided

to students, was a derivative of the English third level system and it enabled

Seamus Heaney to benefit hugely from university education. If Kavanagh had been

born just a few miles north of Inniskeen, on the other side of the border, he

too would have been able to go to university and he would have turned out to have

been an entirely different kind of person and poet. He might well have shared a

little of Heaney’s urbanity and sophistication, but the question remains: if

Kavanagh had become a smooth talking urbanite would his poetry have been as

good?

Instead, he remained

a Monagahan man at heart and to some extent a bumpkin. He never grew out of his

crude manners. Towards the end of his life, he often went to the old Horseshoe

Café in Upper Baggot Street; this was very popular with people like office

staff from the nearby ESB headquarters. If Kavanagh arrived and the place was

full, he had a neat trick for getting a seat. He merely stood in the middle of

the floor and harrumped and wheezed a little and the patrons of the café

disappeared with remarkable alacrity, leaving Kavanagh a good choice of seats.

In those days, when

many middleclass households still had live-in servants, those in houses along

Lower Baggot Street dreaded seeing the approach of Patrick Kavanagh. They knew

that if they had just washed the front steps of the houses they worked in, Kavanagh

would enjoy nothing so much as spitting all over them.

One aspect of

Kavanagh’s life that’s hardly mentioned in polite company - I’m going to put

right that omission now - is his sex life, which I’ve already alluded to. That

astute and brilliant biographer of Kavanagh, Antoinette Quinn, recalled that in

his younger days, Kavanagh had quite an active sex life. Quinn recalled that he

took up with a woman called Peggy Gough, who came from a wealthy family and who

worked as an editor in Browne & Nolan. She had very advanced views for her

time; even though she was engaged to be married, she was quite happy to have

sex with Patrick Kavanagh, even though he was as awkward as a scarecrow and had

as little finesse as he had in his social interactions. Strangely enough, in

his younger days, Patrick Kavanagh had quite an obsession with sex and in those

days, it just wasn’t talked about, let alone acted upon. In a poem he wrote

about Lough Derg in 1942 he had a Franciscan priest there having sex on three occasions

with an innocent schoolgirl.

Much later in life, when

Archbishop McDaid, the devilish Catholic archbishop of Dublin, was one of the

few souls who cared for Patrick Kavanagh and tried to help him out, Kavanagh

did something unthinkable. One day, the archbishop arrived in his official car

outside Kavanagh’s flat at 62, Pembroke Road with a bottle of whiskey and

various other goodies. The archbishop sent his driver up the steps to deliver

them, but Kavanagh just wouldn’t answer the door. It turned out that he was

engaged in sexual congress with one of the prostitutes who did their business

along the banks of the nearby Grand Canal and Kavanagh was damned if he was

going to be interrupted, even though it meant foregoing a bottle of whiskey.

He always seemed to

have a trollop at the back of his mind! One occasion, recalled the late Hugh

Leonard, a media party that included himself and Kavanagh was on its way back

to Dublin from Rome. Kavanagh must have been a stand out figure in the clerical

circles he met in Rome and there is certainly little evidence that he ever gave

religion much thought. When, on the plane back home, Kavanagh wasn’t immediately

served the half bottle of whiskey he had ordered, he called the stewardess an

English bitch and a trollop, to her embarrassment and that of nearby

passengers.

One of the other

great characteristics of Kavanagh is that he had a great gift for screwing up

the many opportunities that presented themselves. He and his brother Peter

didn’t arrived to live in Dublin until just before the outbreak of the second

world war. Yet before they had even landed in Dublin, Kavanagh had managed to

make his debut with Radio Eireann in 1936,and worked soon afterwards with the

BBC in Belfast. He also spent quite a bit of time in literary circles in London

and had also managed to start contributing to The Irish Times. A little later, in

June, 1943, he managed to get work as an extra when the film of Henry V was

being shot on the Powerscourt Estate in County Wicklow.

From here, he went on

to write first for the Irish Press, and then for the Catholic Standard. Some of

his journalist work consisted of writing film reviews and Kavanagh became

notorious for writing some of his reviews without ever bothering to go and see

the films he was talking about. Kavanagh had a great propensity for getting

great opportunities and never sticking with them, ending up by being thoroughly

rude and cantakerous to the people who had the power of commissioning, never a

good idea even at the best of times.

Talking of the Catholic

Standard reminds me that I met, just once, the man who when editor, gave

Kavanagh a steady job for a good while, before the inevitable falling out. In

the late 1940s,Peadar Curry was one of the gods of the publishing business in

Dublin, courted by many who sought favours. When I met him in the late 1980s, to

interview him for a book I was doing on newspaper history, he still remembered

Kavanagh well, and rather fondly, considering Kavanagh’s often disruptive

behaviour at the paper. Peadar was still his hospitable self and pulled out a

bottle of whiskey so that we could have a drink together. But he was living in

indescribable squalor in a caravan park in Rathfarnham for down and out elderly

and disabled people. Peadar Curry’s was a prime example of a falling from grace,

yet he bore his very straightened circumstances as benignly as he could. That’s

all digressing a little, so back to the man of the moment, the loud mouthed and

crude Patrick Kavanagh, and his survival during the second world war.

The poet managed to

do reasonably well during the Emergency period of the second world war and he

also managed to mix in the right circles, during the war, or the emergency as

we liked to call it, with people like John Betjeman, then the press attaché at

the British diplomatic legation in Dublin. Betjeman much later told me how much

he had enjoyed his stay in Ireland during the war and the great variety of

artistic characters he had met, but it was typical of Kavanagh that he wasn’t

able to follow through with Betjeman. Not only did Kavanagh manage to insult

many people, with lasting harm to himself, but his most public falling out was

with Brendan Behan.

Behan was an

ex-jailbird, a vehement republican, a working class hero and a bisexual, all

things that Kavanagh totally despised. Behan in turn saw Kavanagh as little

more than a bad tempered, dirty mouthed culchie.

Yet somehow, Kavanagh

always managed to dismantle things, even when they were going well. His

behaviour was coarse and abrasive, his language foul, his equivalent of a

bramble hedge thrown up to protext his privacy. Trouble was never far away-as

the result of one article in the Irish Farmers Journal, he got thrown into the

Grand Canal, but somehow, managed to escape not much the worse for wear, just

as he managed to survive lung cancer in the mid-1950s.

There was also a

gentler side to him, not often recalled. When the Wee Stores was open in

Pembroke Lane - the premises is now First Editions run by that very good friend

of mine and yours, Allan Gregory, Mrs Harrison, who was the owner’s wife, was

friendly with Kavanagh. She came from County Monaghan and she and Patrick

Kavanagh often conversed in Monaghan dialect, which was clearly much to the

great poet’s liking. The Wee Stores clearly brought out a much gentler side to

Kavanagh.

But he always had

rough and ready survival instincts and he never shook off County Monaghan. He

lived in this part of Dublin from 1939 until his death, but his rural ways

never vanished. One story I heard about him concerns the boiled eggs he always

had for his breakfast-he used the hot water to shave with!

It took him years to

find financial stability and he didn’t acquire a chequebook until 1959,eight

years before his death. Andy Ryan who ran the Waterloo Bar in Upper Baggot

Street for many years told me once of the general astonishment there one day

when Patrick Kavanagh tried to pay for his drinks with a cheque, which needless

to remark, knowing his track record, was refused. He still had to pay cash. Ironically,

towards the end of his life, he was writing for very respected publications, such

as the Farmers Journal and Creation, a very upmarket fashion magazine, and he

even made some very presentable television performances for the then new

television service, Telefís Éireann.

Towards the end of

his life, redemption came in the shape of Katherine, niece of Kevin Barry. They

had lived together for a good few years, but didn’t get married until shortly

before his death. Typically,at his wedding in Rathgar, he walked out of the

church leaving his new wife standing while he himself was totally unaware of

what he was doing. Their last abode together was a garden flat at Number 67

Waterloo Road and there, his last summer on earth was a time of serenity and

contentment. Strangely enough, while plaques were put upon two of his

residences, in Pembroke Road and in Raglan Road, none was ever erected at his

last place of residence.

That summer, in 1967,

was a final, brief, golden era for Kavanagh. Like all golden eras, it ended

quickly. In recent years, despite the recession, we have been living in a

something of a golden era, which seems to have evaporated very suddenly this

year following the Russian takeover of Crimea in March.

Typically of

Kavanagh, the last public event he attended ended in a shambolic row. On

November 18, 1967, he was at the unveiling of the Wolfe Tone memorial on St

Stephen’s Green. He sat on a reserved seat and promptly got into a scuffle with

an attendant. Charles Haughey tried to intervene, but to no avail, and Kavanagh

promptly went home and wept. To the very end of his life, he felt he was being

dishonoured in the city of his adoption, not given the recognition he felt was

his due. He had less than a fortnight to live and after he died at the

end of that November, he was buried from Haddington Road church. After the

Mass, the cortege headed along Pembroke Road, Raglan Road and Waterloo Road

before travelling to his native Iniskeen, where he was buried.

As soon as Patrick

Kavanagh died, he was hailed in the newspapers as the greatest Irish poet since

Yeats. How he would have snorted at all the praise heaped upon him, which had

to wait until his death to be said.

I’ve concentrated

very much on Kavanagh the man, his follies and his foibles, for the simple

reason that I find those much more interesting than critical analyses of his

work. But the man makes the poet. It’s rather ironic these days that the rough

hewn man of Monaghan soil, so vulgar and lacking in social graces, has had

those rough edges smoothed over. We acknowledge the brilliance of his poetry, which

is as it should be, as for instance, his poem about Raglan Road, which as a

song, sung by the late Luke Kelly, is firmly cemented in the public

imagination. But I think that in the modern iphone era, Kavanagh has been

sanitised, his rough edges so flattened and smoothed out that what we see now

is almost a two dimensional parody of the real man and the hidden poet. His

statue on the seat on the banks of the Grand Canal, even his remembrance in his

native Inniskeen, also now seem diminished into a two dimensional format.

The internet, digital

age has reduced everyone’s level of emotional intelligence to that of a baby, when

what we need to really appreciate Kavanagh for who he was and what he did, is

to revel in the crudity, the profanity, the lack of manners and the boorishness

of the poet from Iniskeen, because that is what all what made him such a great

poet, one of the greatest Ireland has ever produced.

Delivered to the Irish Byron Society, at the United Arts Club, Dublin 2, April

25th., 2014

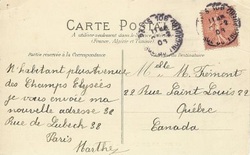

Hugh Oram’s French blog

The book of Hugh Oram’s French blogs will be published in the US by Trafford Publishing on February 7, 2014, as both a printed book and as a downloadable ebook.

Hugh, who is a media journalist, author and journalist, based in Dublin, has made innumerable visits to France over the past 50 years and with his wife, Bernadette, who worked at the Foreign Ministry in Dublin, has visited every department of mainland France, as well as most of the islands off the French coast.

While they have made innumerable visits to Paris, where they usually stay in the 7th., they’ve also travelled extensively round France. Both are fluent in French and apart from his visits to France, Hugh tracks news and developments in France on a daily basis. Among the many publishers for whom he has worked are Éditions Michelin in Paris.

To him, the daily news agenda in Paris and France is as familiar with that of his home territory of Ireland and just over a year ago, he decided to put this interest and knowledge to good use by writing a weekly blog about France. To him, the map of Paris is every bit as familiar as that of Dublin,where he and his wife live.

His sister, Emma Louise Oram, has played a big part in all this, because she posts the blogs every week and sources the illustrations. Taking the blog further, Hugh then decided to put them into book form, so that readers could find all the material gathered together, with each week’s blog forming a separate chapter. However, the book is text only; the illustrations haven’t been included.

The end result is the book of blogs, which covers the period from November, 2012 until November 2013. "The production deadlines mean that the love scandal with the French president and incidents like the activist dumping a lorryload of steaming manure outside the Assemblée Nationale in the seventh came too late for inclusion. But the terrific thing about France is that a good scandal or otherwise great news story seems to pop up every five minutes or so, which helps keep the blog going”, says Hugh.

Each chapter in the book and ebook is clearly inscribed with the date of the original blog and a suitable headline. As an example, the very first chapter in the book is headlined: "Murder and Mayhem in Corsica". It starts by describing a political murder on the troubled island a few days before the blog was written. The chapter also details how this pair of intrepid travellers got caught up in a raid by an armed gang on a hotel in Corsica. In between all this news reporting, Hugh talks much about what Corsica is really like as a tourist destination and this sets the pattern for the rest of the book.

In the book, he details his many experiences in travelling through France as it really is, not as the idealised country of some public relations handout.

From that point of view, the book, since it covers many different regions, will give travellers and holidaymakers some unique insights into the joys and sometimes the pitfalls of holidaying in France. His advice and information is always down to earth and very much to the point.

Neither does he spare French politicians,and especially the French president, M.Hollande, whose popularity ratings have hit an all-time low as the country wallows in a continuing recession. Politicians elsewhere, including in the UK, Ireland and the US, come in for the same hard hitting scrutiny and this whole editorial mix is leavened with lots of stories and anecdotes.

If you want to find out more of what France is really like or merely confirm your existing experiences in this fascinating country, this is the place to start. After all, despite all its grinding bureaucracy and often poor customer service, France remains the world’s top tourism destination.

Hugh Oram’s French blogs, November 2012-November 2013, can be ordered from Trafford Publishing, Amazon, Barnes and Noble and other online booksellers, as well as from your local bookshop. The retail price for the book, in US dollars, is $20.00, while the ebook download is priced at $3.99.